An Bhean Chaointe

Background

Video clip above by kind permission ITMA (c) 2006

(see A Hidden Ulster pp. 137-150 for detailed references and information)

This ‘jewel of a song‘, as described by the folksong collector, Dr Tom Munnelly, is a song in the keening tradition which is unique to the Oriel tradition. It was collected in Omeath and in Crossmaglen. No other versions, other than those collected in Armagh and Louth, are found in the song tradition of Ireland, although some of the motifs are found in other laments.

Women were the main carriers of keening songs, and there is evidence that it was practised widely in the Oriel region. The collector Lorcán O Muirí (AHU pp. 358-60) wrote it down from a number of women, Mrs Caithtí Nic Guibhirín, (Kitty McGivern) (AHU pp. 407) and Mrs Caithtí Sheáin Dobbins (AHU pp. 403-4) with some verses from Éamonn Ó hAnnluain in Omeath (AHU pp. 404-5).

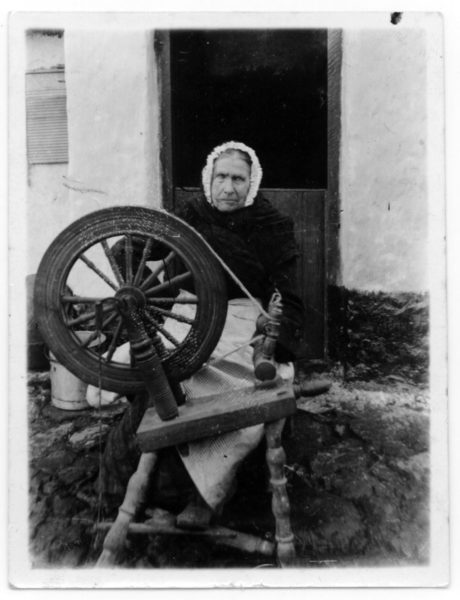

Photo of Caithtí Bean Mhic Ghuibhrín sometimes mistaken for photo Mrs Nancy Caulfield, another singer and storyteller from Omeath. Photo: Peadar Ó Dubhda. copyright A Hidden Ulster 2017

He published it in tonic solfa in 1927 in his song collection Amhráin Chúige Uladh. The song collector Donn Piatt (AHU p. 382) who gave some songs to Lorcán Ó Muirí urged him to publish it:

Ba cheart duit A Neillí Bháin go mbeannuighidh Dia dhuit a chur ar An tUltach go luath. Tá sé go hálainn agus ba cheart na rudaí is fearr a chur amach go luath … tá rud inteacht an-phatetic, an-truacánta fá Neillí Bhán agus Séamas Mhac Murchaidh.

You should publish A Neillí Bhán in An tUltach soon. It is beautiful and you should publish the best soon … there is something very pathetic, very sad about Neillí Bhán and Séamas Mhac Mhurchaidh. Donn Piatt (AHU p. 382)

A spoken version was collected by Wilhelm Doegan in 1931 of Caithtí Uí Ghuibhrín (pictured), recorded in 1931 for the Doegen sound recording project giving an example of Omeath Irish. She was aged 85 at the time.

Mrs Caithtí Sheáin Dobbins, who sang An Bhean Chaointe. (AHU 140). copyright A Hidden Ulster 2017

It is one of the great songs of southeast Ulster and is not found elsewhere in the Irish song tradition. The song expresses the broad spectrum of human emotion – intense passion, anguish and grief, love and tenderness as well as jealousy, anger, hate and revenge.

The story, which was told in Omeath, is of a woman who had twelve children and when eleven of them had died she lost her reason and took to the roads. Later on she meets up with some young women on their way to a wake house and joins them. In the house she is treated as a beggar woman and given potatoes from a pot, which had been prepared for the pigs. This insult brings her to her senses and she recognizes her own home and that she is at the wake of her youngest daughter, Nelly. She makes this lament.

Though the keening tradition died out in the latter half of the nineteenth century in Ireland, there is strong evidence of an active tradition in the southeast Ulster region, not only with the survival of this song but from other accounts as well. The manner of keening varied, and so did the song material.. The various accounts of keening in the locality would suggest that there were different forms of keening, set to different types of song, sung at different times of the wake and funeral. In Omeath the keening women sang and composed various lamentations depending on the circumstances of death. Some of the keening took the form of sung prayers, suggesting a chant over the corpse.

Mrs Margaret Modartha Kelly – the last known keening woman in south Armagh. copyright A Hidden Ulster.2017

The dead person was keened at various times during the wake. As soon as the body was prepared and laid out, the family would keen for ten minutes. Keening then took place by hired mourners as darkness fell, after the saying of prayers and finally at daybreak. The formal keening was usually performed by semi-professional women though not exclusively so, and was carried out with ritual and ceremony. During the eighteenth century, the tradition was strong in the southeast Ulster area and a number of accounts have been given by people who lived locally and by others who witnessed the keening.

The last known woman heard keening over the dead in the south Armagh area was Margaret Modartha Kelly (AHU pp.398-9) from Carrickasticken, Forkhill, who lived by the river near Urney graveyard.

The song is closely related to songs of the keening tradition and shares many of its motifs. In latter times laments such as this and other songs such as Amhran na Páise, (AHU pp.319-23) Luan a’ tSléibhe (AHU pp.324-7) would have been sung at funerals and wakes. An account is given of three women in Omeath who sang Caoineadh na dTrí Muire over a corps and who ‘gathered at the bedside and with their hands stretched on the corpse chanted twice what was known as the Song of the Three Virgins.’ ( AHU p. 321).

In Foughil near Dromintee in County Armagh, one woman recalled,

‘I heard it sung in Irish when I was a wee thing at a wake house in Foughil. It was three women or girls sung it over the corpse. One stood at each side of the coffin and one stood at the head. And they joined their hands over like that (demonstrating arms crossing at the wrists) and kept them like that while they sung the Seven Joys to make a cross over the corpse‘ (AHU pp. 321-2).

In Omeath the female descendants of the seventeenth-century poet Séamus Dall Mac Cuarta (AHU pp. 337-43) who were known to be poets as well, were the hereditary keening women or mná caointe of Omeath. Peig Nic Cuarta, the last of them died about 1860 ‘leaving a reputation for power of invective and vigour of description that the Dall himself would have envied’.

Oriel Arts © CÉ 2019

Transmission

Traditional singer Pádraigin Ní Uallacháin sourced the song from the 1927, Lorcán Ó Muirí collection of songs, Amhráin Chúige Uladh in tonic solfa. She first recorded it on the Gael Linn CD An Dara Craicean 1995. The above opening video was filmed by Irish Traditional Music Archives during Sean Nós Cois Life 2005.

Traditional singer Pádraigin Ní Uallacháin sourced the song from the 1927, Lorcán Ó Muirí collection of songs, Amhráin Chúige Uladh in tonic solfa. She first recorded it on the Gael Linn CD An Dara Craicean 1995. The above opening video was filmed by Irish Traditional Music Archives during Sean Nós Cois Life 2005.

Lorcán Ó Muirí recorded An Bhean Chaointe on phonograph from Mrs Kitty McGivern and Nancy Caulfield, Omeath, and with verses too from Mrs Dobbin (Cití Sheáin) and Éamonn O’Hanlon.

Seán Ó hAnnáin collected a version from Brigid Hearty in Clarnagh, Crossmaglen in 1905. He wrote down verses from her and also in phonetic form giving an indication of the local pronunciation. Luke Donnellan collected a version in a recititive style variant of the same melody, from the Hearty/McKeown family in Lough Ross, Crossmaglen.

It is recorded in full on Ceoltaí Oirialla -Songs of Oriel CD 2017.

Seán Ó hAnnáin manuscript from Brigid Hearty, Lough Ross Crossmaglen 1905. Copyright A Hidden Ulster

Seán O hAnnáin manuscript in phonetic pronunciation from Brigid Hearty/McKeown 1905. Copyright A Hidden Ulster

Oriel Arts © Ceoltaí Éireann 2018

Words

Sources (edited from):

- An Bhean Chaointe: Amhráin Chúge Uladh 1927,1 from Mrs Dobbin (Cití Sheáin). Mrs Kitty McGivern and Éamonn Ó Hanlon, Omeath.

- An Bhean Chaointe: from Brigid Hearty, Clarnagh, Crossmaglen.

- Mo Nighean na Míne: Seán Ó hAnnáin MSS in Ó Fiaich Library, Armagh.

An Bhean Chaointe

A Neillí bhán dheas, go mbeannaí Dia d(h)uit!

Go mbeannaí ’n ghealach bhán ’s an ghrian d(h)uit!

Go mbeannaí na haingil ’tá i bhflaitheas Dé d(h)uit!

Mar a bheannaíonn(s) do mháthair bhocht a chaill a ciall dhuit.

D’oil mé is d’fhulaing mise dáréag leanbh,

D’fhan mé ’na ndiaidh lena nigheadh is lena nglanadh,

D’fhan mé ’na ndiaidh lena gcur faoi leacacha,

Is a níon is míne, mo mhíle creathach.

Fuair mise cuireadh nuair a tháinig mé ’un mur sráide;

Fuair mise cuireadh, ach cuireadh gan fháilte é;

Fuair mise cuireadh chuig bascaod na bpreátaí;

Och, ’á mairfeadh mo níon chumainn, gheobhainn cuireadh is fáilte.

Chan cuireadh mná comónta a fuair mé ar mur sráide

Ach an cuireadh a fuair mise, cuireadh gan fháilte é,

Cuireadh ’mo shuí mé ag bascaod na bpréataí,

Och, ’á mairfeadh mo níon pháirte, gheobhainn cuireadh ’na pharlúis.

A Neillí bhán dheas, go mbeannaí Dia d(h)uit!

Go mbeannaí an Rí ’s an tAthair Síoraí d(h)uit!

Go mbeannaí ’n ghrian ’s an ghealach siar ’s aniar d(h)uit!

Mar a bheannaíonn(s) do mháthair bhocht a chaill a ciall dhuit.

A chailín óg thall a rinn’ an gáire,

Nár fhágaidh tú an saol seo go bhfaighe tú croí cráite,

Fá mise bheith ’g éagaoin fá mo níon na páirte,

Bheas ag dul uaim amárach i gcórthaí clárthaí.

Och, a bhean úd thall, ’riú is duit is fusa,

Beidh do mhacsa pósta le céile eile –

Maighdean óg deas i mbun a leapa

Is mo níon is mo théagar ag dul faoi leaca’.

Dá bhfuireo(cha)dh do níon i mbun a pósta,

Fuair sí céile gan dronn gan chomhartha,

Fuair sí togha agus rogha na dóighe

Agus an tír seo thíos uilig faoina comhairle.

Och, a chailín óig atá a’ déanamh díom meithghéim gáirí,

Nár fhágaidh tú an saol seo go bhfaighe tú ábhar gola ’n áit gáire,

Fá mise ag éagaoin mo níon na páirte,

Bheas ar shiúl ’na gcreagacha maidin amárach.

Éirigh, ’Eoghain, agus muscail Róise,

’S a Mháire na gcumann, bí tusa leofa,

Dhéanfaidh Síle dheas an chomhra a chóiriú,

Agus cuirfi muinn Neillí bheag i ndeireadh a’ tórraimh.

Ó, rachaidh mise amárach go cruinniú a’ phobail

Agus muscló’ mé na mná greadta atá i bhfad ’na gcodladh;

Bhéarfaidh mé ’na bhaile na mná so-chorrtha

Agus cuirfidh mé ar shiúl na mná síochánach’.

Tá an ghrian ’s a’ ghealach ag triall faoi smúid;

Tá réaltaí na maidne ag sileadh na súl;

Tá na spéarthaí in airde fá chulaith chumhaidh

Is go dtillfidh tú aríst cha luíonn an drúcht.

The Keening Woman

Fair Nelly, may God bless you!

May the white moon and the sun bless you!

May the angels in God’s heaven bless you!

As your poor mother who lost her reason for you, blesses you.

I bore and raised twelve children,

I stayed with them to wash and clean them,

I stayed with them to bury them beneath slabs,

Now fair daughter my thousand tremblings.

I was invited when I came in to your street;

I was invited but without a welcome;

I was invited to the potato basket;

If my beloved daughter lived, I’d be invited and made welcome.

It was not the invitation of ordinary women I got here

But the invitation I got was without a welcome.

I was sat down at the potato basket;

If my daughter lived, I would be invited to the parlour.

Oh fair Nelly, may God bless you!

May the King and the Eternal Father bless you!

May the sun and the moon, east and west bless you!

As your poor mother who lost her reason over you, blesses you

Young girl over there who made the laughter

May you not leave this world till your heart is tormented,

At my lamenting my beloved daughter,

Who will be leaving me tomorrow in a wooden coffin.

Oh woman over there, it is easy for you,

Your son will be married to another spouse –

A nice young virgin about the bed

And my daughter and my darling going under slabs.

If your daughter had but stayed about her marriage

She found a spouse who was honest and upstanding;

She got the best and the choicest of ways,

And the country all about at her command.

Oh young girl who is making a mockery of me,

May you never leave this world till your laughter turns to tears,

At my lamenting my darling daughter,

Who will be walking the rocks tomorrow morning.

Rise up, Eoghan, and wake up, Róise,

And, dear Máire, you go with them,

Fair Síle will prepare the coffin

And we will bury little Nelly after the wake.

I will go to the gathering of the people tomorrow

And I will awake the keening women who are long asleep;

I will bring home the excitable women

And I will send away the peaceful women.

The sun and the moon are moving in shadows;

Teardrops fall from the morning stars;

The skies above are in a cloak of sorrow

And until you return again the dew does not lie.

Translation: Pádraigín Ní Uallacháin

Oriel Arts © Ceoltaí Éireann 2018

Music

Sources:

- An Bhean Chaointe: Lorcan Ó Muirí. Amhráin Chúige Uladh, 1927, 1, from Kitty McGivern, Omeath.

It is a recitative type air that is found in older ABBA song form. The air of the song is similar to other older airs associated with laments in the area: it is simple, plaintive and chant-like. It is in the metre of keening songs and echoes the older tradition of extempore lamentation, though here the verses are made up of regular four lines as distinct from irregular verses such as that found in Caoineadh Art Uí Laoire (The Lament of Art O’Leary).

Oriel Arts © Ceoltaí Éireann 2018

Amhráin Chúige Uladh 1927