Marbhna nó Cumha

Sources

The following contribution is by ORIEL ARTS harper, Sylvia Crawford. See also her description of the Early Irish Harp in Oriel Harpers section here.

In the video she is playing a HHSI Student Otway harp (on loan from The Historical Harp Society of Ireland), made by David Kortier (USA) and modelled on the Otway harp. The Otway (or Castle Otway) harp, was once owned by Oriel harper, Patrick Quin, and is now owned by Trinity College, Dublin.

Sylvia Crawford playing early Irish harp with fingernails. Photo: Brenda Malloy

‘This piece of music came from the playing of Oriel harper, Patrick Quin, which was collected by Edward Bunting c.1800. Bunting’s own annotated volume of his 1809 publication also contains a note written under the piano arrangement of Marbhna no Cumba – A Death Song. It reads ‘Another of the old Caoinans sung at funerals’.

Marbhna no Cumha – A Death Song is not the title of the tune, but rather an indication of the tune type, as a lament. I have not yet come across any evidence to suggest that Quin also sang with the harp, as some of the harpers did, but we do know that he played the fiddle, and that he played in his locality for weddings and funerals (Bunting 1840). The fact that Bunting wrote ‘Tune name unknown‘ in his notebook, may also suggest that Quin played the air only, and did not sing it.

I based my playing of this tune on an air entitled ‘Tune name unknown‘, from Bunting’s MS 33(1), f33r / p.65 (upside down). There are three pieces of information which link this tune to the Armagh harper, Patrick Quin. Like Lochaber, this tune belongs to a group of tunes, written upside down, at the back of MS 33(1). These tunes are believed to have been collected by Edward Bunting from Patrick Quin in County Armagh around 1800; one of the tunes in this group is Quin’s Burns March (or Pretty Peggy), and all but one of the other tunes in this group are cited elsewhere as having been collected from Quin.

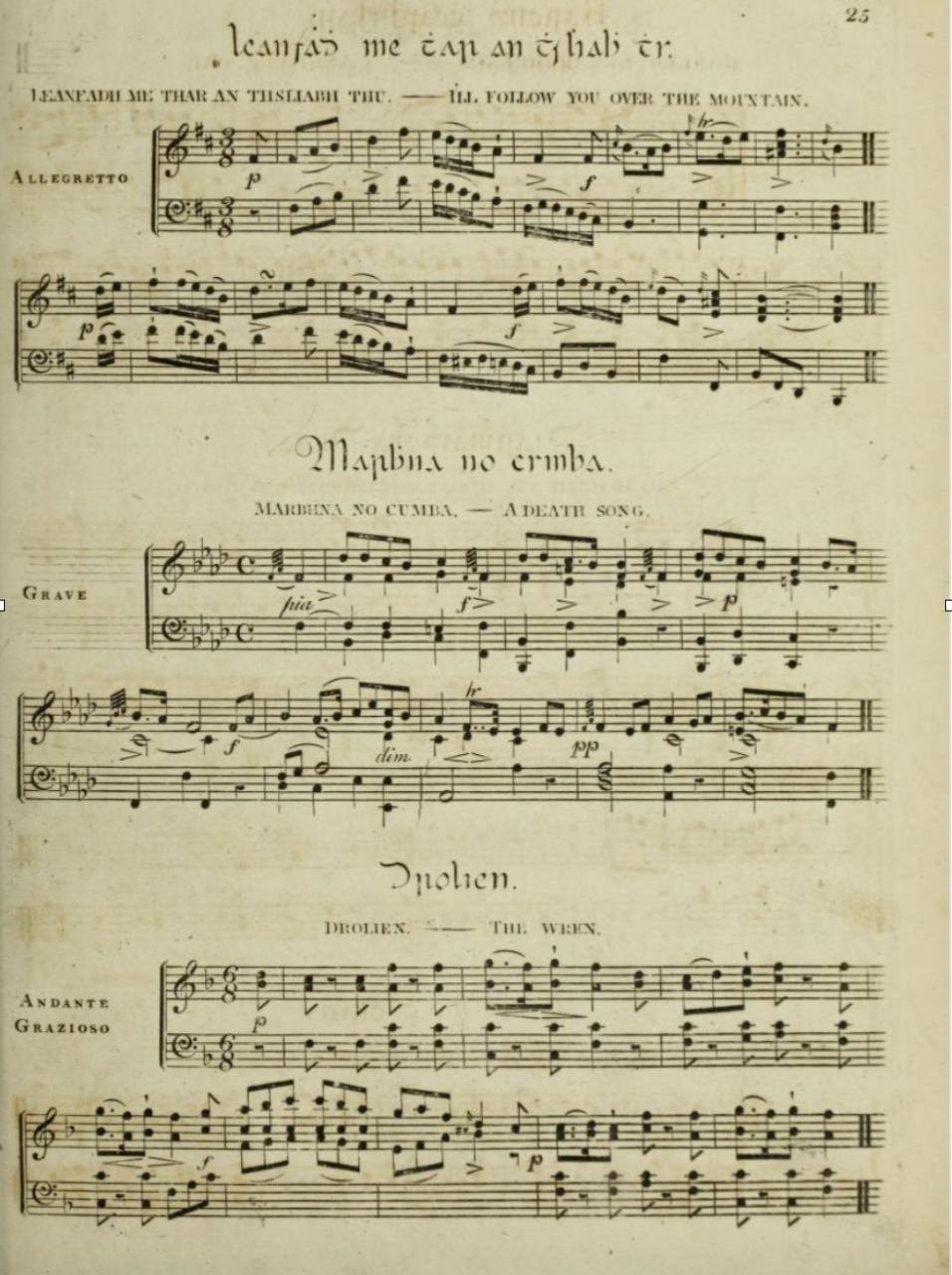

The second piece of evidence linking this tune to Quin is in a later manuscript (MS 12), which is Bunting’s preparation for publication. It is again marked ‘Tune Name Unknown‘, but is also marked ‘death song‘ and ‘from Quin‘. The tune was published in A General Collection of the Ancient Irish Music (Bunting 1809) under the title Marbhna no Cumba [Cumha] – A Death Song.

The third confirmation that this tune came from the playing of Patrick Quin is in Bunting’s own copy of his 1809 publication, discovered in the British Library (BL Addl 41508) in 2009 by Dr. Karen Loomis, where Bunting has written ‘Quin Harp‘ beside this tune.

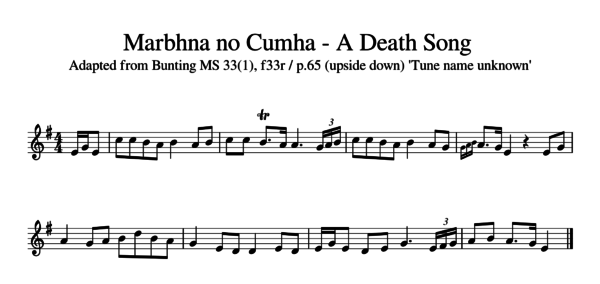

Notation

The MS 33(1) draft, on which I base my transcription, appears in the treble only. On first glance it appears to be relatively straightforward and legible. However, the lack of key signature is problematic, and involves some detective work. The tune begins and ends on F, but there is no key signature indicated. Bunting’s piano arrangement also begins and ends on F, but four flats are indicated. His harmonisation suggests F minor, and he includes E naturals on occasions in the accompaniment, whilst retaining E flats in the melody. It is not possible to alter the pitch of a string on an early Irish harp, therefore this is not a plausible key. Nor could this have been how Quin played the tune on his harp.

O’Sullivan’s transcription of the tune also uses a key signature of four flats, with F as the first and last notes. Rather than this suggesting F minor, I think it suggests the B flat dorian mode. If we apply the same principle, as with the other tunes in this group, and set the tune down one note (or one tone), that would put it into A flat Dorian. But neither of these keys would be suitable for an early Irish harp.

I propose therefore that the missing key signature in MS 33(1), p.65 ‘Tune name unknown’, is three sharps. This would suggest B Dorian mode. Following the principle of moving this down one tone, would put the tune in A Dorian, which has one sharp (F sharp). This is what the harpers described as the ‘natural’ key for the harp.

My transcription is adapted from MS 33(1), p.65. For the above reasons, I have set it in A Dorian, a note lower than the manuscript version. In bars 2 and 7 there are not enough beats. As a possible solution, I added a triplet symbol to the last three semiquavers, and made the third beat a dotted crotchet. Alternatively, the last three notes could be made into triplet quavers (rather than semiquavers), or two semiquavers followed by a quaver.

My playing of this tune (in the video) incorporates elements of the melody shape and rhythm from the printed piano version. Here I am playing the tune in D Dorian, which also works on an early Irish harp.

Unlike the song and fiddle traditions, the Irish harp does not survive in a continuous, unbroken tradition. The harp was a high status instrument in Ireland for many centuries, with a highly developed oral tradition. However, by the end of the eighteenth century, the Irish harp, was dying out. Various attempts were made throughout the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries to revive the old traditions, but these proved unsuccessful for a number of different reasons.

The early Irish harp, played by the harpers mentioned in A Hidden Ulster, was different in many ways from modern harps. The early Irish harp has metal strings, tuned diatonically, with no mechanisms for altering the pitch of a string, other than the tuning pegs. Two strings in the middle range of the harp are tuned to the same pitch, referred to as ‘na comhluighe‘ (or ‘sisters’ or ‘lying together’). It is traditionally played on the left shoulder, (the opposite to modern Irish harps), with the left hand in the treble and the right hand in the bass.

At the gathering of harpers in Belfast in 1792, only one harper, Dennis O’Hampsey, the oldest, played with the old fingernail style. All the other harpers played with their fingertips.

Because the oral tradition for the harp was lost, practitioners of this instrument rely on early manuscript sources and written accounts of the playing of the early harpers, for the reconstruction of this tradition, both for repertoire and for insight into playing techniques. The value of Edward Bunting’s work lies primarily in his field transcriptions of tunes taken directly from the old harpers, and in his observations of their manner of playing.

Although incomplete and second hand, this is, nonetheless, a very valuable source. Other aspects that contribute to the process of reconstructing the harp tradition, include a knowledge of related traditions (particularly song and piping, which remain unbroken and which have archive recordings), examining the surviving harps that are housed in museums, making and playing replicas of these harps, examining the portraits of the old harpers with their instruments for indications of posture and hand position, etc.’

Oriel arts 2018 ©Sylvia Crawford

References

- Simon Chadwick (2017). Patrick Quin (c.1745 – early nineteenth century) [online]. Available from http://www.earlygaelicharp.info [accessed 12 April 2017].

- Academia (2017). (LOOMIS, K 2010). Edward Bunting’s Annotated Volumes of Irish Music: An Overlooked Treasure at the British Library [online]. Available from http://academia.edu [accessed 13 April 2017]

- O’SULLIVAN, D. (1927). The Bunting Collection of Irish Folk Music and Songs. Journal of the Irish Folk Song Society (ed. 1967). Vol IV, pp.81-82.

- MOLONEY, C. (2000). The Irish Music Manuscripts of Edward Bunting 1773-1843. An Introduction and Catalogue. Dublin: Ceol Taisce Dúchais Éireann (Irish Traditional Music Archive).

- BUNTING, E. (1809). A General Collection of the Ancient Irish Music. London and Dublin.

- London, British Library BL Addl 41508 Bunting Collections 1809.

- The Library at Queens, Special Collections MS 4/12, Bunting Manuscript Collection.

- The Library at Queens, Special Collections MS 4/33(1), Bunting Manuscript Collection.

- BUNTING, E. (1840). The Ancient Music of Ireland, Arranged for the Piano Forte. Dublin.

- NÍ UALLACHÁIN, P. (2005). A Hidden Ulster. People, songs and traditions of Oriel. Four Courts Press.

Music

Sylvia Crawford transcription, Marbhna nó Cumha. Copyright Sylvia Crawford 2017

MS 33(1) p.65 upside down. By kind permission Queens University Special Collections 2017

1809 printed piano version p. 25